Enlarge image i

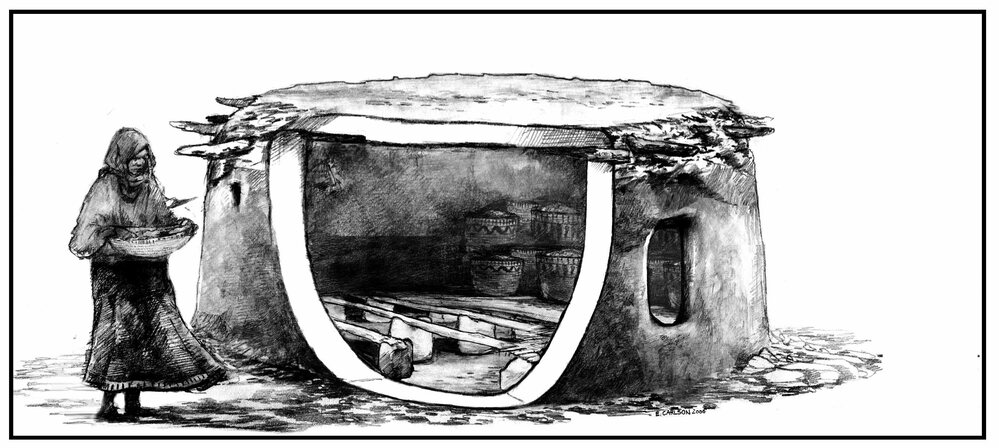

Enlarge image i Prehistoric "pantries": This illustration is based on archaeological findings in Jordan of structures built to store extra grain some 11,000-12,000 years ago.

Prehistoric "pantries": This illustration is based on archaeological findings in Jordan of structures built to store extra grain some 11,000-12,000 years ago.

For decades, scientists have believed our ancestors took up farming some 12,000 years ago because it was a more efficient way of getting food. But a growing body of research suggests that wasn't the case at all.

"We know that the first farmers were shorter, they were more prone to disease than the hunter-gatherers," says Samuel Bowles, the director of the Behavioral Sciences Program at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, describing recent archeological research.

Bowles' own work has found that the earliest farmers expended way more calories in growing food than they did in hunting and gathering it. "When you add it all up, it was not a bargain," says Bowles.

So why farm? Bowles lays out his theory in a new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The reasons are complex, but they revolve around the concept of private property.

Think of these early farmers as prehistoric suburbanites of sorts. The first farmers emerged in less than a dozen spots in Asia and South America. Bowles says they were already living in small villages. They owned their houses and other objects, like jewelry, boats, and a range of tools, including fishing gear.

They still hunted and foraged, but they didn't have to venture far for food: They had picked fertile places to settle down, and so food was abundant. For example, one group in what is present-day Iraq lived close to a gazelle migration route. During migration season, it was easy pickings they killed more animals than they could eat in one sitting. They also harvested more grain from wild plants than they knew what to do with. And so, they built "pantries" structures where they could store the extra food.

Enlarge image i

Enlarge image i The granary uncovered at 'Dhra, Jordan, illustrates that people stored wild grain before even before they were farming it.

The granary uncovered at 'Dhra, Jordan, illustrates that people stored wild grain before even before they were farming it.

These societies had seen the value of owning stuff they were already recognizing "private property rights," says Bowles. That's a big transition from nomadic cultures, which by and large don't recognize individual property. All resources, even in modern day hunter-gatherers, are shared with everyone in the community.

But the good times didn't last forever in these pre-historic villages. In some places, the weather changed for the worse. In other places, the animals either changed their migratory route, or dwindled in numbers.

At this point, Bowles says these communities had a choice: They could either return to a nomadic lifestyle, or stay put in the villages they had built and "use their knowledge of seeds and how they grow, and the possibility of domesticating animals."

Stay put, they did. And over time, they also grew in numbers. Why? Because the early farmers had one advantage over their nomadic cousins: Raising kids is much less work when one isn't constantly on the move. And so, they could and did have more children.

In other words, early cultures that recognized private property gave people a reason to plant roots in one place and invent farming and stick with it despite its initial failures.

Bowles admits this is just an informed theory. But to test it, he and his colleague, Jung-Kyoo Choi, built a mathematical model that simulated social and environmental conditions among early hunter-gatherers. In this simulation, farming evolved only in groups that recognized private property rights. What's more, in the simulations, once farming met private property, the two reinforced each other and spread through the world.

Bowles' theory offers a more nuanced explanation that ties together cultural, environmental and technological realities facing those first farmers, says Ian Kuijt, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame.

But, he says the challenge is to figure out who owned the property back then and how they ran it. "Was it owned by one individual?" Kuijt says. "Was it a mother and father and their children? ... Does it represent community or village property?"

Dan Gilbert: The surprising science of happiness Video on TED.com Dan Gilbert, author of "Stumbling on Happiness," challenges the idea that well be miserable if we dont get what we want. Our "psychological immune system" lets ... What Are Parabens And Why Should You Avoid Them. What are parabens? You may have heard about how you should avoid parabens in the products you buy, but you might be wondering why you should do so. Ran Prieur Ran Prieur "The bigger you build the bonfire, the more darkness is revealed." - Terence McKenna io9 - We come from the future. One of the most violent and wondrous cosmic events is starburst, in which hundreds of millions of stars are born all at once. These are far rarer nowadays than they ... io9 - We come from the future. We come from the future. ... Superman or Nietzschean Superman? Jos Quintero's Allegorical Superheroes series places costumed superheroes in philosophical or ... Because I'm Black...: Why are black people so loud when they are ... Q: I work on a college campus and see black students standing around talking loudly/yelling at each other and at people that are walking by them. The Matrix (1999) - IMDb Quotes on IMDb: Memorable quotes and exchanges from movies, TV series and more... Video - Breaking News Videos from CNN.com The latest video from CNN and its networks on breaking news stories. Secrets of the Phallus: Why Is the Penis Shaped Like That ... If youve ever had a good, long look at the human phallus, whether yours or someone elses, youve probably scratched your head over such a peculiarly shaped ... Data - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Data are values of qualitative or quantitative variables, belonging to a set of items. Data in computing (or data processing) are represented in a structure, often ...

No comments:

Post a Comment